What happens when the Imperial Core loses its Neocolonies?

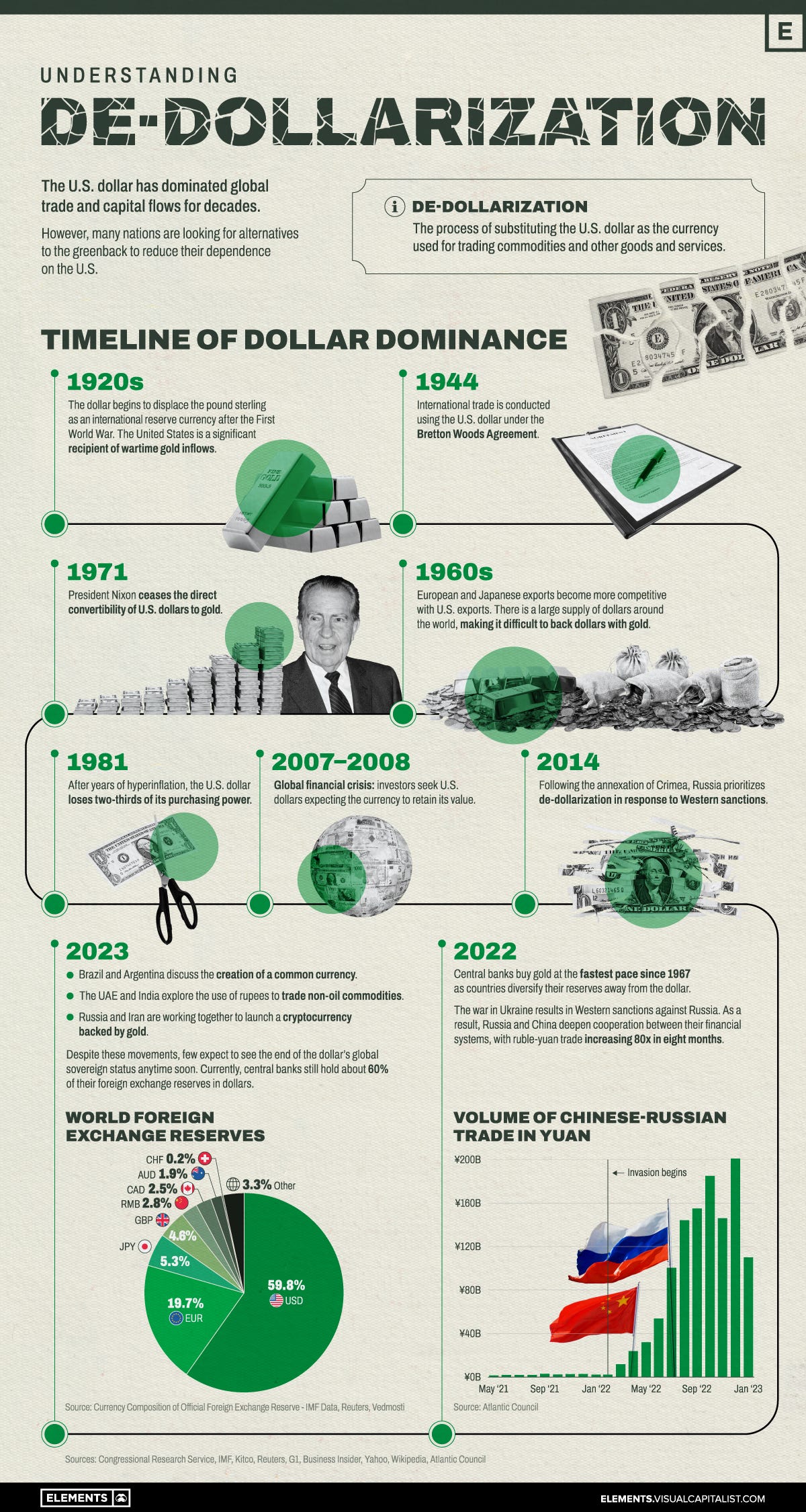

Headlines today are filled with trepidation at the term “de-dollarization.” Hidden behind the headlines is the potential consequence of this process, of nations choosing to rid their dependence on the US dollar and western networks of trade.

The global market is today experiencing de-dollarization and splits into multipolar trade networks with no single country as globally predominant. To prepare ourselves for proper activity in the face of resulting political crises, we will analyze the consequences of these imperial losses in the context of two primarily contradictory tendencies, which drive the oncoming economic crises in a world finally casting off the old chains of neocolonialism and neoliberalism. First, we must define what is meant by the “imperial/neocolonial world system,” provide a brief history of its exploitative nature, and then we will analyze the tendencies that are driving its final collapse.

What is the “imperial world system?” What is “neocolonialism?”

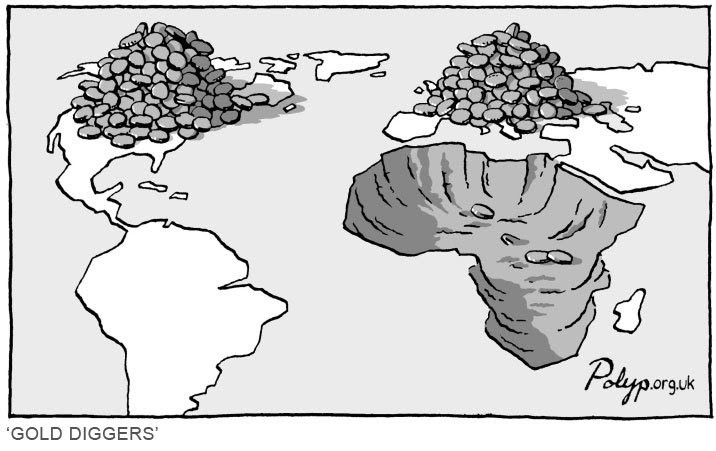

In his book The Sword and the Dollar, published during the neoliberal heights of the Reagan administration, Michael Parenti defined the imperial world as a “Condominium Empire” dominated by primarily US multinationals, “along with firms of other advanced capitalist nations,” which “control most of the wealth, labor, and markets of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.” The specific methods of control have evolved over time, but the general structure of imperialism as defined by Lenin in 1917 remains mostly the same: monopoly capital directed by a financial oligarchy, accumulating through the global extension of credit and domination of supply chains. Parenti continues from Lenin’s analysis into the age of neocolonialism: “This control does much to maldevelop the weaker nations in ways that are severely detrimental to the life chances of the common people of the Third World.”

By “maldevelopment,” Parenti means US financial “aid” and investment pointed towards continued dependency on the imperial core. It is a “sharp philanthropy” that really only aids the richest people in poor countries— compradors to the imperialists. In the post-war period, European powers were forced to replace direct colonial administration over annexed territories with “neocolonialism,” or rather ownership of wealth, exploitation of labor and resources, and control of markets and state policies through indirect instruments like capital exports and currency regimes. As the colonists pulled out, relationships were maintained with the native colonial administrators and bureaucrats, who kept their place in the hierarchy in exchange for keeping their nations open for imperialist capital flows. As Kwame Nkrumah defines it, “foreign capital is used for the exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world. Investment, under neo-colonialism, increases, rather than decreases, the gap between the rich and the poor countries of the world.” Capital flows into poor countries never seem to help the countries pull themselves out of poverty. Instead, they create a cycle of dependency where countries must keep borrowing in order to pay interest on accumulating debts.

“Development” banks dominated by western imperialists, like the IMF and World Bank, provide a prime example of the policies of neocolonialism. These banks condition their investments on terms that ultimately hold the Third World back from sovereign economic development. When the World Bank makes a loan, it will make sure that loan goes toward building ports and airstrips meant solely to ship raw materials out of “underdeveloped” nations, rather than allowing these nations to use capital to industrialize or develop trade routes with each other. If the IMF is to extend a credit line to a struggling economy, it will condition that credit on massive privatization and political restructuring that allows western imperialists to more easily access Third World resources and cheap labor. Both of these banks charge usurious interest rates ensuring that the capital loaned out will only result in the need for more loans, at increasingly less-favorable terms, as these nations sink ever further into debt crisis. Struggling nations can only afford to pay interest on accumulating debts and buy more oil, or else face default and economic stagnation. Oil producers profiting on poor oil importers then buy US treasury bonds with their increasing dollar surpluses. This is called “petrodollar recycling,” as dollars lent out immediately return to lenders and the US government. Oil importers must keep large dollar reserves on hand to keep their economies running, and the value of the US dollar is floated by its high demand.

Unlimited capital liquidity and the predominance of the US dollar are held sacred, not only to maintain profit accumulation but also to maintain the accumulation process, the systems of ownership and dependency that assure future capital accumulation. To ensure the holy accumulation process, the imperial core builds a “military security system to safeguard the international social order that maintains and expands this capital accumulation process.” Aid and access to western capital is conditioned on military agreements to station troops, build military bases, and host trainings for Third World national militaries. These enforcers of neocolonialism are important to counteract the rising resentment and oncoming crises due to these policies. The crises are in turn inevitable due to contradictory tendencies inherent to neocolonial control and extraction.

What are these tendencies?

The tools of neocolonial extraction today face criticism unheard since the fall of the Soviet Union. Masses in imperialized countries today are drawn into escalating revolts against the economic crises resulting from neocolonial control. Even the national bourgeoisies in these countries are beginning to turn away from the western imperial trade network. How do these revolts contribute to the tendencies toward neocolonial collapse?

(1) The mass of workers available to the trade networks maintained by the neocolonial powers (mainly the US and Western Europe), which depend on cheap labor and maximum capital liquidity, are going to become less and less available to foreign exploitation. Neocolonial policies that have dominated the global economy for decades have led to the outsourcing of production to nations where labor is easier to exploit. Peripheral nations were forced to open their borders for maximum extraction by the imperial core, of cheap labor and raw materials.

This has led to a growing awareness and resistance to exploitation in imperialized countries. The colonized nations join rivaling trade blocs and shun the old “development banks” that in the period of neoliberal victory have maintained labor and resource extraction at the major benefit of the US dollar (and, correspondingly, anyone who happens to have access to a stable supply of US dollars). Countries today want to trade in national currencies, not in paper that can easily be folded into weapons against those who earn imperial ire. Neocolonies today see opportunities to control their own development in the final period of imperialist decay, and those who seize it will starve the traditional western exploiters of the circuits that have long pumped fresh blood into their economies. The value of the US dollar, inflated with speculation on what profits can be maintained on the vampiric imperial world system, will collapse.

(2) The amount of labor exploitation must necessarily increase if profit potential is to be preserved. This is because profit potential is mostly speculative among financiers (measured in debts, rents, and other “obligations”), and a loss of ownership in the wake of decolonization means that both real and speculative value for multinational corporations and creditors is all lost.

In other words, the neocolonial model relies on the exploitation of cheap labor and raw materials in developing countries to generate profits for Western corporations and investors. This model is unsustainable in the long term, as developing countries demand sovereignty over their resources and labor. When they detach the instruments of extraction from their national economies, they shrink the means of production and mass of labor available to those long used to superprofits at the expense of the global south. The corresponding crisis in capital necessitates a struggle amongst the imperial owners for the scraps they are still left with, a struggle that can only be maintained on the backs of the remaining mass of labor still under the imperial owners’ thumbs. The same resentment that led to imperial value chain detachments from the imperial periphery is shifted onto workers in the imperial core.

Karl Marx in his theory of surplus value describes these contradictory tendencies in the early period of European capitalist competition. As Marx explains in chapter 11 of Capital, "if the mass of labor power employed [...] increases, but not in proportion to the fall in the rate of surplus value, the mass of the surplus value produced falls." In other (oppositely pointed) words, if the amount of labor power and raw material extraction employed in the neocolonial world system decreases (due to growing decolonial national consciousness in escalating class warfare), but the rate of domestic labor exploitation increases at a pace that doesn’t catch up (due to a corresponding escalation in class warfare within imperial core workforces), then the total surplus value generated will decrease. In order to maintain profits, imperial core owners and financiers must ratchet up labor exploitation within the sphere that they still control, which risks raising class consciousness to militant levels wherever this heightened exploitation becomes most localized. If they don’t, they risk losing their market share, or losing the systems of domination that still enable their existence. Debts and obligations must still command respect, or else other groups suffering austerity will get ideas about their own liberation.

History shows us in miniature what happens to capitalists who lose their net worths in the wake of decolonization. Herbert Hoover lost a significant portion of his net worth in the wake of the Russian Revolution. The future President Hoover had invested heavily in Russian industries, as had many French and English financiers prior to World War I. When the Bolsheviks seized power and nationalized these industries, Hoover lost his investments and was forced to write off large amounts of debt. His net worth shrank by several million dollars.

Each circuit of finance and investment detached from renters being sucked dry means a whole class of wealth no longer accessible to financiers, and consequently a whole army of canceled debts. Embittered financiers must scramble to preserve the circuits of capital they still have left, which become increasingly insular and under ever-increasing amounts of pressure as the dream of liberation spreads.

How does this relate to today?

When nations declare the nationalization of their resources, as much of Latin America is doing today, or when nations spurn dollar trade for national currencies, as Saudi Arabia is currently offering to do (heralding the death of the petrodollar), the circuits of capital that feed western financiers shrink and break, necessitating an increase in exploitation somewhere else, or the centralization of the remaining capital hoards into ever fewer hands, to make up the losses. When nations choose not to denominate trade in dollars anymore, they render this formerly hot commodity obsolete.

If the imperial core loses easy access to lithium, the supply chains that feed into battery production must account for increased costs. If banks fail because they have to write off debts to a bankrupted industry (for example, tech industries having trouble coping with losing cheap lithium that their balance sheets were counting on), their assets will be acquired for a song by the surviving banks. The middle classes and petty capitalists are swallowed by the financiers with most control over credit and debts. The surviving financiers by no means escape the consequences of spreading collapse. Much of their acquired assets turn toxic, and the small band of surviving financiers realize that very few debts they own are ever going to be repaid. Their bloated hoard of capital faces ever fewer avenues for profit accumulation, so financiers are loath to extend it anywhere at all, but its removal from circulation in turn signals a massive economic depression. The imperialist strategy of financialization, with no domestic industrial production to fall back on, reveals itself to be the shoddiest of foundations as profitability collapses. The crisis further feeds into de-dollarization and nationalization of resources as international capitalists (up to now all too happy denominating their wealth in dollars) note the US’s increasing financial instability.

Already we see the beginnings of financial panic as medium-sized banks teeter and collapse in this year’s first quarter. Predictably, the larger banks snap up the failures, as we saw this past week with First Republic’s acquisition by JP Morgan Chase. As inflation shows no signs of slowing, the big banks cannibalize the medium and small banks as quickly as possible. Hedge funds controlled by the big banks short-sell smaller bank stocks, driving them to the brink for easier acquisition (see: There Was a Blood Bath in Some Bank Stocks Yesterday). The Federal Reserve, FDIC, and Treasury are powerless to do anything except keep the asset bubbles inflated that buoy up this country’s false wealth. They can only assist the centralization of finance into the increasingly unstable large private asset firms. Facing external pressure, the internal contradictions in the US financial system begin to crack. Inadequate monetary and fiscal policy measures do nothing to stop the rising tide, and in fact only serve to punch more holes in the boat.

The stability of the western imperial world system is in question as the global market experiences neocolonial collapse. The ultimate factor in the degradation of western capitalism is the contradictory dynamic between the need for cheap labor and maximum capital liquidity, and the growing awareness and resistance to the exploitation of labor and resources in awakening imperialized nations. As our interconnected world is rocked by oncoming crises, the social and environmental costs of imperialist arrogance grow ever more present in the lives of the exploited. The calls for freedom begin in the furthest peripheries, where the most raw material and blood of laborers flows at the most unsustainable rates into capitalist hands, where nature itself revolts against capitalist waste in pursuit of careless profit accumulation. Where the chains of imperial maintenance are weakest, they break first. De-dollarization is an objectively progressive movement in this direction. Calls for freedom spread after the formerly colonized declare liberation from neocolonial bonds. Their calls must be seized up by workers up and down the imperialist value chains, so that the chains can be thrown off by united action against our common exploiters.